Who is the (real) first Computer Programmer?

Because it sure ain't Ada Lovelace.

Ask a majority of computer nerds, “Who was the first computer programmer?” and you’re likely to get one answer more than all others: Lady Ada Lovelace.

But was Ada Lovelace truly the first computer programmer? Or is that idea based on a bad understanding of both history and computers? Let’s dive in and figure this out.

The Work of Ada Lovelace

During the 1800’s a book series entitled “Scientific Memoirs” was published. An 1843 edition of that series included an English translation — of a French publication — of a lecture given by Charles Babbage on his theoretical, mechanical computing machine: The Analytical Engine.

That English translation was done by Ada Lovelace. And, in addition to her translation, she included a handful of notes that were included at the end of the publication.

One of those notes (labeled “Note G”) was a theoretical method for using the Analytical Engine to compute Bernoulli numbers.

This is what that note looked like:

This “Note G” is what many people consider to be the “first computer program”. And, thus, this is what has earned Ada Lovelace the title of “world’s first computer programmer.”

There are, however, a few issues with bestowing this title upon Ada Lovelace.

The computer this program was written for… did not exist. It was purely theoretical. Which means she was never able to actually “program” this “computer”.

The software never “ran”. If a programmer never writes software that runs (not even once)… is that programmer… a programmer?

Charles Babbage, the creator of the designs for this theoretical mechanical computer, also had to conceive of similar ways to utilize the computer. Thus, he would have been the “first programmer”… as he would have done so prior to Lovelace even hearing about the machine designs.

So. Was Ada Lovelace the first computer programmer?

Obviously not. While her writings which documented Babbage’s work are — undoubtedly — critical pieces of computing history (something for which Ada Lovelace deserves to be remembered), she was not a computer programmer. And, therefor, could not have been “the first one”.

So… who was the first programmer?

Ok. So Lovelace was not the first computer programmer. That much is obvious.

Which begs the question… who was?

To answer that we need set a few requirements for determining if someone was, or was not, a computer programmer.

The computer they are writing programs for? It needs to actually exist.

They must have run a program, which they wrote, at least one time on said computer.

Those two requirements seem rather obvious.

Let’s look over a few possibilities…

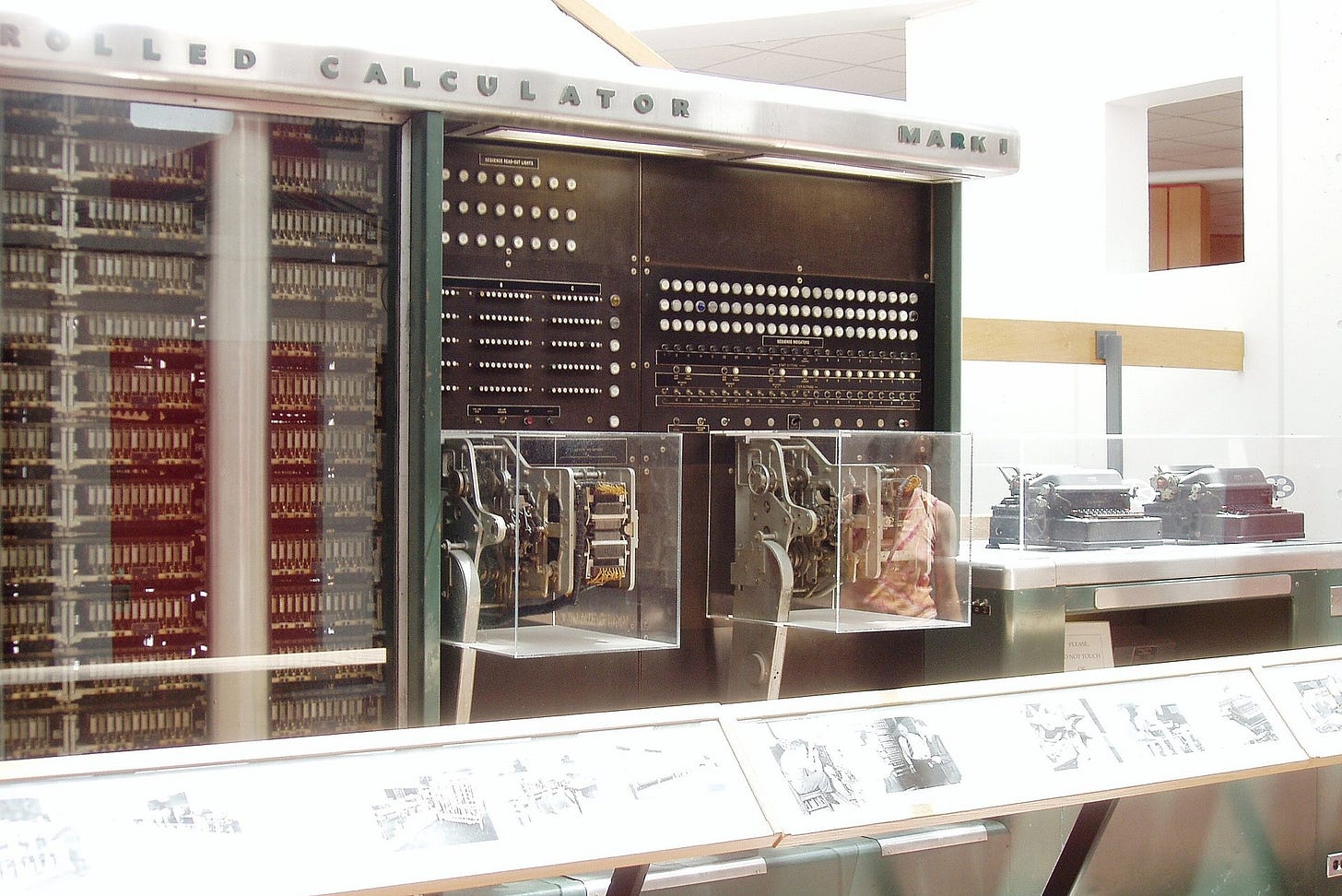

1944 - Programmers of the Mark 1

In 1944, the Mark 1 (at Harvard) went online. This was the first programmable computer in the United States of America.

The first programmers for this machine were: Richard Milton Bloch, Grace Hopper, and Robert Campbell.

In Gary Kildall’s unpublished memoir, the legendary inventor of CP/M and the BIOS related a story about Grace Hopper which includes the line:

“Grace Hopper was self-proclaimed to be the first programmer, and I believe her.”

Being as the Mark 1 was, indeed, programmable — these three programmers are certainly good contenders for the title of “first programmers”. And, among the three (Bloch, Campbell, and Hopper), Hopper appears to be the one who claims the title (without objection from others).

Grace Hopper would go on to be an absolute force within the world of computing (specifically on the development of FLOW-MATIC and COBOL).

However…

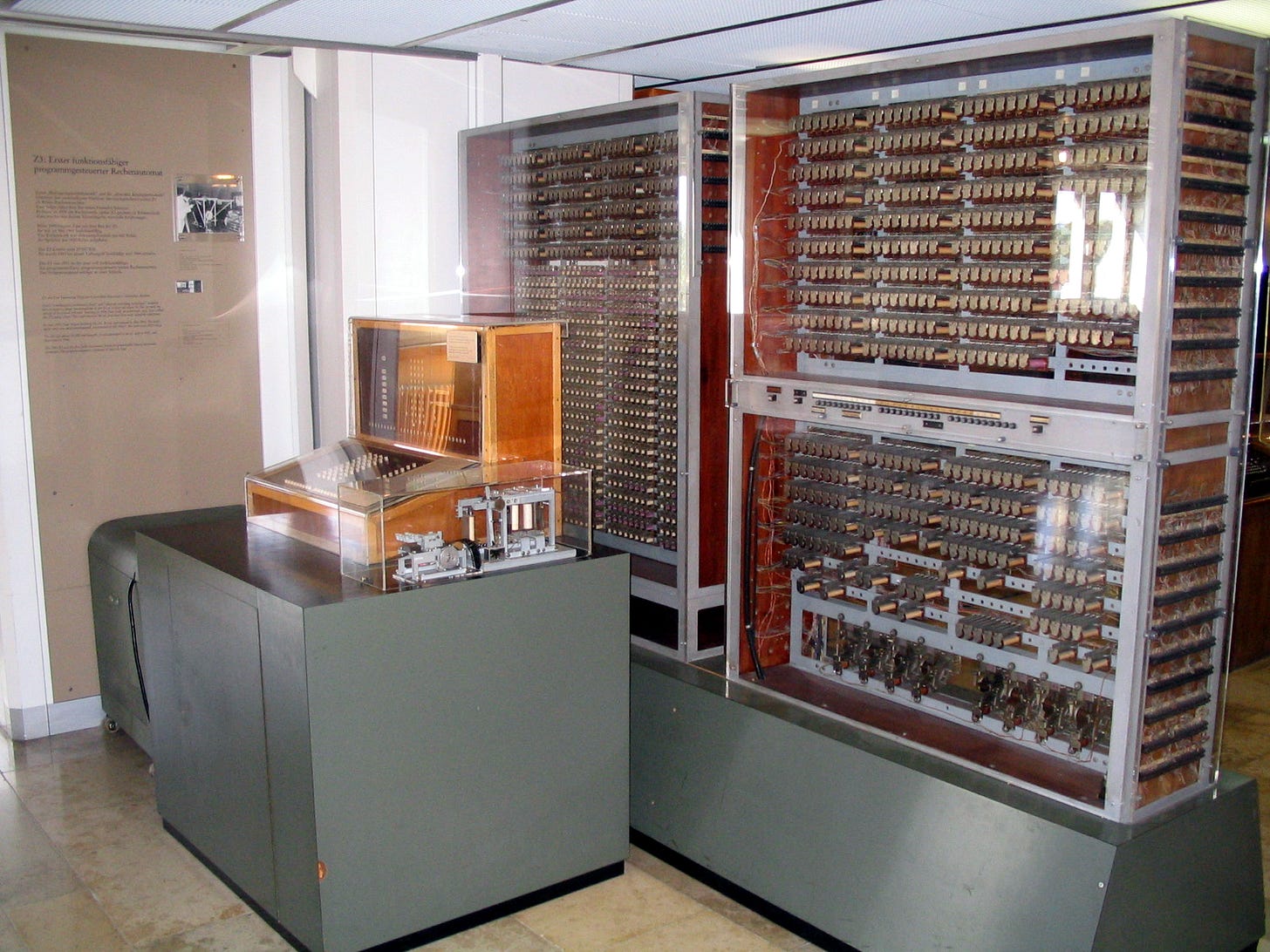

1941 - The Z3

3 years earlier, in 1941, Konrad Zuse had just completed his Z3 computer. An electromechanical machine (similar to the Mark 1 in that regard) that was the first operational, programmable computer in the world.

If this is the first programmable computer — and Konrad Zuse developed it — it stands to reason that Konrad Zuse would have tested the Z3 with programs which he wrote. Thus making Konrad Zuse the first computer programmer in the world.

Something fascinating here:

The work on both the Z3 and Mark 1 was happening during World War 2. The Mark 1 being funded by the United States and the Z3 being funded by Nazi Germany.

Which means that two completely different teams were making computer history… completely separated from each other.

The Truth

The cold, hard truth is that Konrad Zuse, funded by Hitler’s Nazi Germany, is — in all likelihood — the first true computer programmer.

Note: Yes. Zuse was funded by the Nazi government of Germany. Zuse did not object or fight against the Nazis in any noteworthy way, and did significant work inside of Nazi bunkers. He worked with the Nazis willingly and eagerly. Regardless of what we all think of the Nazis — spoiler… we don’t like them — the technical accomplishments of Zuse are real, documented, and should be regarded as a critical part of computing history.

However, the team in the United States would not have known about this. For them, they were the first to have a truly programmable computer with the Mark 1. Upon which, Admiral Grace Hopper claims to have been the first to program.

Now, here’s where things get tricky in defining “Computer Programmer”.

Does the person who built the computer count? Or can this title only be bestowed on someone who programmed the computer… but did not, themselves, build it?

If the builder of the computer counts… Zuse wins the title.

If the builder is disqualified… Hopper is the first computer programmer.

Either way, Ada Lovelace definitely was not the first computer programmer. This much is overwhelmingly obvious.

What is amazing about this fact: Despite seeing the documentation, many will cling (with an almost religious like fervor) to the idea that Lovelace was the first computer programmer. I find that fascinating.

Want more computer history? The kind you aren’t likely to read about anywhere else? Become a subscriber to The Lunduke Journal and get a digital copy of “Lunduke’s History of Computers - Volume 1”.

Konrad Zuse. Yes, i admire this man. Before Z3, there was the first computer he built, all mechanical, and he did so just before the war broke out. His creation was destroyed by the Allied bombing, so he rebuilt it.

Not sure how much Nazi funding would've played a role in the Z3, however, but I will have to check the history on that. I know he mentioned something about it, almost apologetically. In so many words, he did not have too many alternatives at the time. And a man's gotta eat, and so...

Just like the Nazi rocket scientists who went on to build rockets in the US, it's the work that mattered. Wherever you can get the funding, off you go. Not excusing it, but it's reality. It's a thing, I think, you and I may have been tempted to do if under the same circumstances.