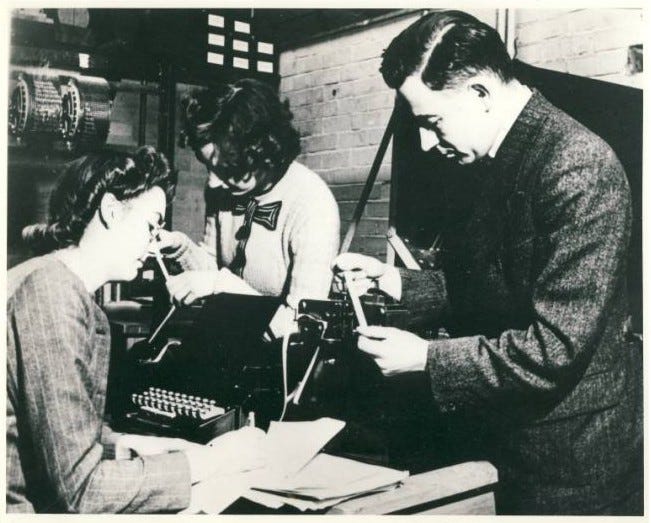

The 1948 precursor to the hard disk

A brass rotating, magnetic drum... inspired by a voice dictation machine.

Floppy disks. Zip disks. Hard disks. These sorts of spinning, magnetic storage mediums have been critical to several decades of computers. It’s almost hard to imagine the computers of the 1970s, 80s, and 90s without floppy disks (and other magnetic drives).

But how, exactly, did they come into existence?

Let’s take a quick look at the very first of such devices… and its inspiration.

1946 - The Mail-a-Voice

We’ll begin our journey with the 1946 release of the Brush Mail-a-Voice.

A truly fascinating device, the Mail-a-Voice looked like a phonograph… except it used a paper disc that was coated in magnetic material. You could then record up to 3 minutes of audio on a single paper disk (which would spin at 20 rpm)… and then fold the paper disc up and mail it inside a standard envelope.

Thus the “Mail-a-Voice”.

This device didn’t store computer data itself… but it did inspire engineers who were working on cheap data storage for computers…

February, 1948 - Andrew Booth’s Spinning Drum

In a 1947 trip to the USA, Andrew Booth (who was working on his own computer design), had the chance to see the “Mail-a-Voice” in action.

Since Booth needed a good, inexpensive storage medium for his computer… he attempted to build a similar device using a flat, paper, magnetic disk. What was, essentially, a first attempt at what we would now call a “Floppy Disk”.

Unfortunately, it didn’t quite work. Booth found that he needed to spin the paper disk quite a bit faster in order to make it viable as a data storage mechanism… and he had a hard time keeping the paper disk flat.

In fact, as Booth upped the RPM to 3,000 — which is what he determined he needed — the paper disk itself started to disintegrate. Booth would later comment:

“I suppose I really invented the floppy disc, it was a real flop!”

So he abandoned that approach and, instead, decided to use a brass drum. Because brass is a bit less likely to disintegrate than… paper.

This system worked. His brass, rotating drum (with a magnetic coating), had a 2 inch diameter and could store 10 bits per inch.

Yeah. 10 bits. Per inch.

Not exactly massive amounts of storage. But, hey, it was a start! And it didn’t disintegrate! Huzzah!

Improving the magnetic drum

With the first prototype working, Booth set about improving this magnetic, rotating drum storage device. The final version ended up being able to store 256 words of either 20 or 21 bits each (different sources cite different values here and there does not appear to be consensus on if it was 20 or 21 bit words).

This storage drum was put to use on the ARC (the Automatic Relay Computer).

When all was said and done, the ARC could utilize that storage drum to handle 50 numbers and could load a program consisting of 300 individual instructions.

It wasn't exactly a “Hard Disk Drive”… more of a “Hard Drum Drive”.

Either way… Pretty darn cool for the 1940s.

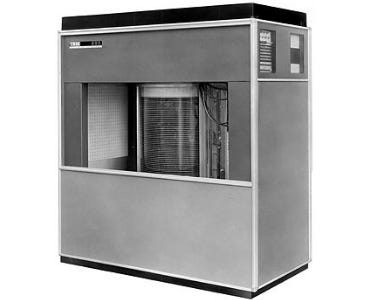

1956 - The First “Hard Disk Drive”

Over the years that followed, this idea was refined and improved. The rotating drum was abandoned for hard, magnetic platters — ones sturdy enough to handle much higher RPMs (and thus leading to faster data access).

Eventually leading to the 1956 release of the IBM Model 350 Disk Storage Unit for the IBM 305 RAMAC computer.

The Model 350 Hard Disk Drive, in a base configuration, could store roughly 3.75 MB — all contained in a cabinet 5 feet long, 2 1/2 feet deep, and 5 1/2 feet tall — with platters spinning at 1,200 RPM.

And all thanks to a voice dictation device built for sending 3 minutes of audio on a piece of paper.

The Lunduke Journal Community — About the Lunduke Journal — Subscriber Perks

The Lunduke Journal Weekly Schedule:

Monday - Computer History

Tuesday - Computer & Linux Satire

Wednesday - Podcast (Subscriber Exclusive)

Thursday - Computer History (Subscriber Exclusive)

Friday - Wildcard day! Anything goes!

Saturday - Linux, Alternative OS, & Retro Computer News Article

Sunday - Linux, Alternative OS, & Retro Computer News Podcast

That’s fascinating history that I’d never heard anywhere before. Thanks Mr Lunduke!