No Backup: The demise of physical media

From "Backup Floppies" to "No Physical Media" in 40 years.

Over the last several decades, there have been many changes and shifts in the world of computing.

Processors and architectures. Physical form factors. Networking types. User interfaces. So many changes have come and gone that one can be forgiven for forgetting more than one remembers.

While many of those shifts have had dramatic impacts on how we use our computers — with both negative and positive aspects — there is one such change which has been so overwhelming negative… it borders on the disastrous:

The almost total demise of physical media.

Where once software could be obtained on floppies, CDs, and DVDs… now software can only be obtained as online-only, digital files — often wrapped in a system of Digital Rights Management — that are as ephemeral as footprints in the sand. Lasting only until a digital store goes offline… or a company goes out of business… or we simply loose access to the Internet.

We have gone from software being available on physical media, which could be backed up and stored by end users… to a digital dystopia where we have an ever-decreasing control over our software… in just 40 years.

And it didn’t happen by accident.

This is a free article. Want more of the truly independent Tech Journalism from The Lunduke Journal? Lunduke Journal subscribers get a mountain of goodies — and have access to all of the in-depth, premium articles, such as these recent ones:

The 1970s - Micro-Soft, Apple, & differing approaches to software

While this story could almost start at any point in the vast history of digital computing, things really get their foundations in the 1970s.

During this time, personal computing was seen more as a hobby than anything else. Computer enthusiasts across the land built their own computers (often from kits), and gathered together in local computer groups and clubs — where they traded software, documentation, dreams, and ideas.

Here we find the beginning of when people truly began to turn personal computers into a viable business.

And here we find distinctly different approaches to the software for those computers.

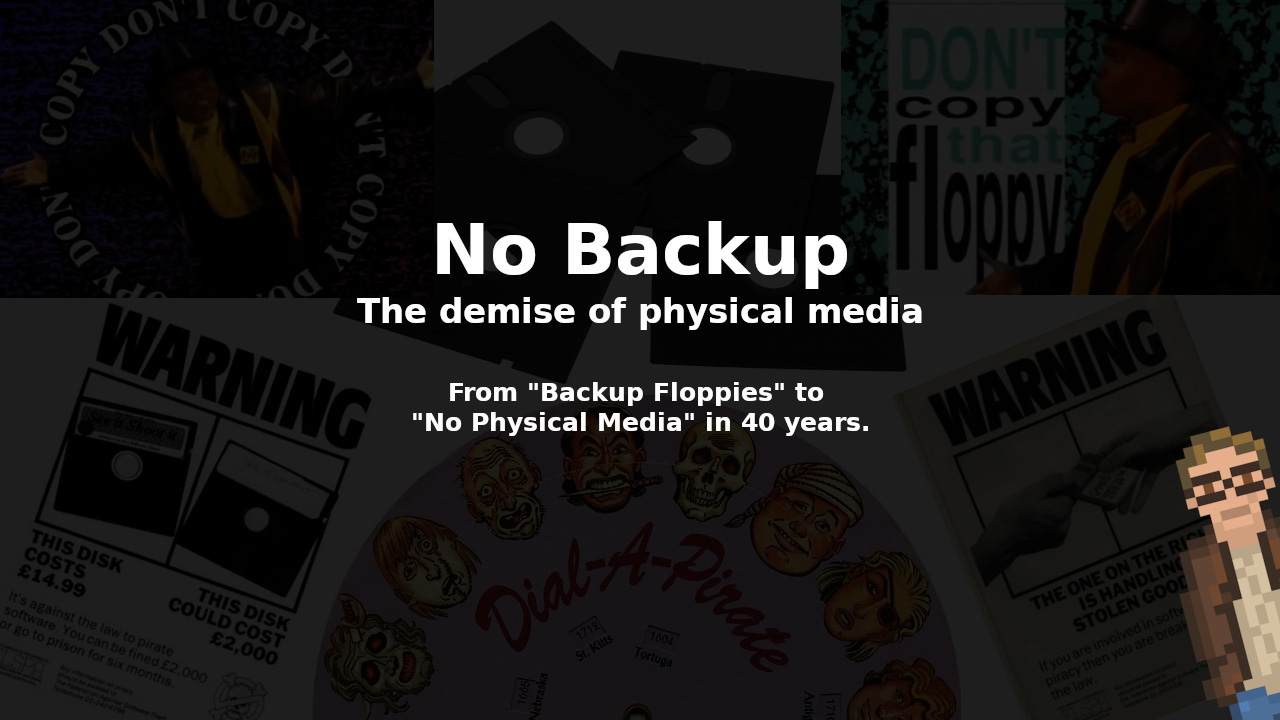

On the one hand, we have the prevailing attitudes of the computer clubs — echoed by the newly formed Apple Computer — that software should be readily available (and, preferably, free). From Apple Computer’s early advertisements:

“A tape of APPLE BASIC is included free with the Cassette Interface. … Also available now are a dis-assembler and many games, with many software packages, (including a macro assembler) in the works. And since our philosophy is to provide software for our machines free or at minimal cost, you won’t be continually paying for access to this growing software library.”

How was this software provided? On physical media, of course. In those days, this often meant cassette tapes and printed code (such as in the various computer newsletters) — with 5 1/4” floppy disks appearing in 1976 (and gaining high levels of usage by the end of the 1970s).

The focus on making software easy to obtain — and easy to copy — made tremendous sense for both the computer hobbyists and the hardware companies. There simply was not a large quantity of software available for the various personal computers that were being created.

More readily (and cheaply) available software made the computers — which were, otherwise, simply electricity-sucking hunks of metal — actually useful. And, hence, this meant more hardware sales.

On the other hand, we had the small companies that were attempting to turn “making personal computer software” into a profitable business all by itself.

One of the biggest examples was Micro-Soft (yes, “Microsoft” was spelled with a hyphen back then), who was responsible for creating the first high level programming language (BASIC) for the Altair 8800 (the first successful, commercial personal computer).

In essence: Micro-Soft’s software made the Altair 8800 infinitely more useful.

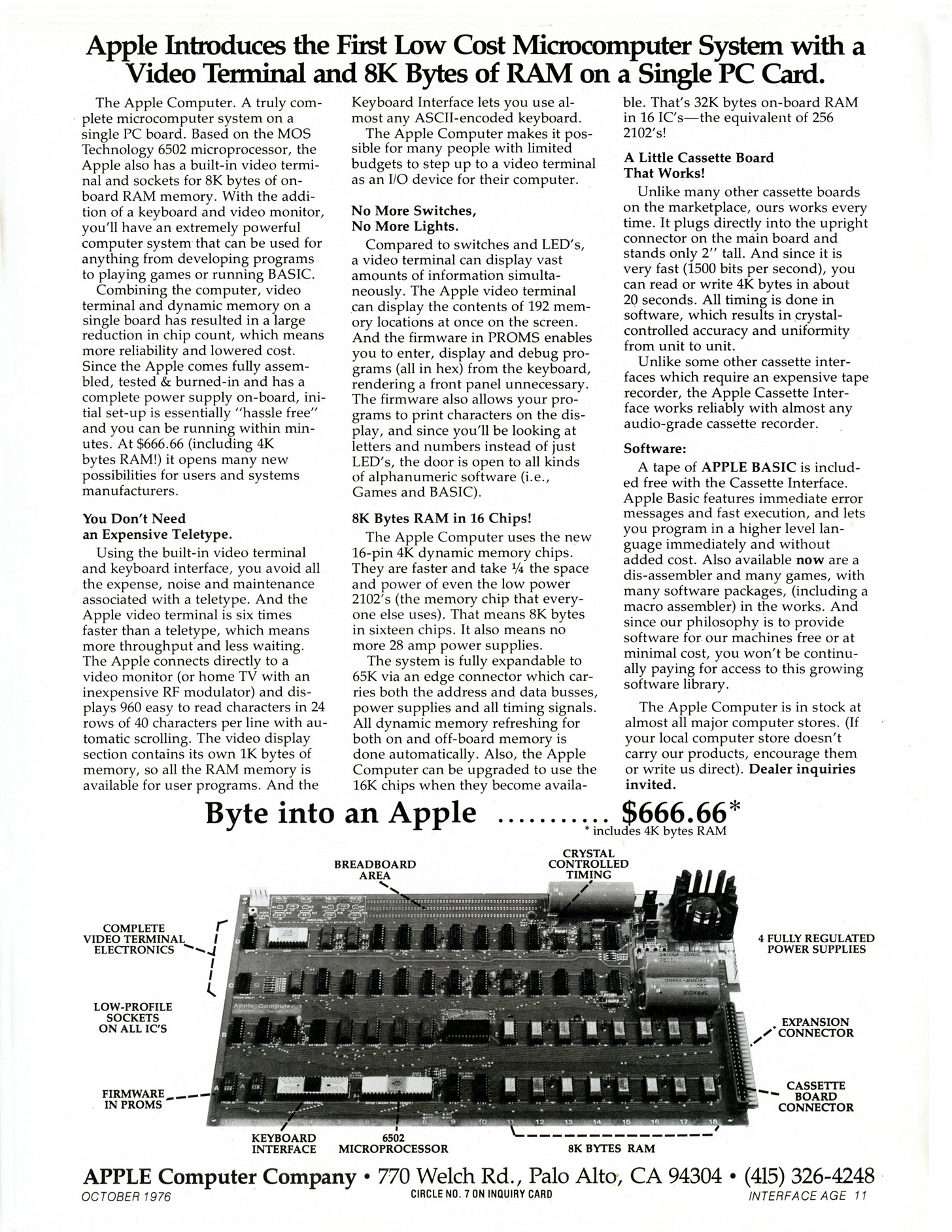

Unfortunately for Micro-Soft… people were not buying “Micro-Soft BASIC” for the Altair. They were copying it. At computer clubs. Which prompted Bill Gates to write an open letter to computer hobbyists to talk about this problem… and encourage people to go buy software.

And, right here, is where the stage is set for the eventual eradication of physical media for computer software. Seriously. This is a pivotal moment.

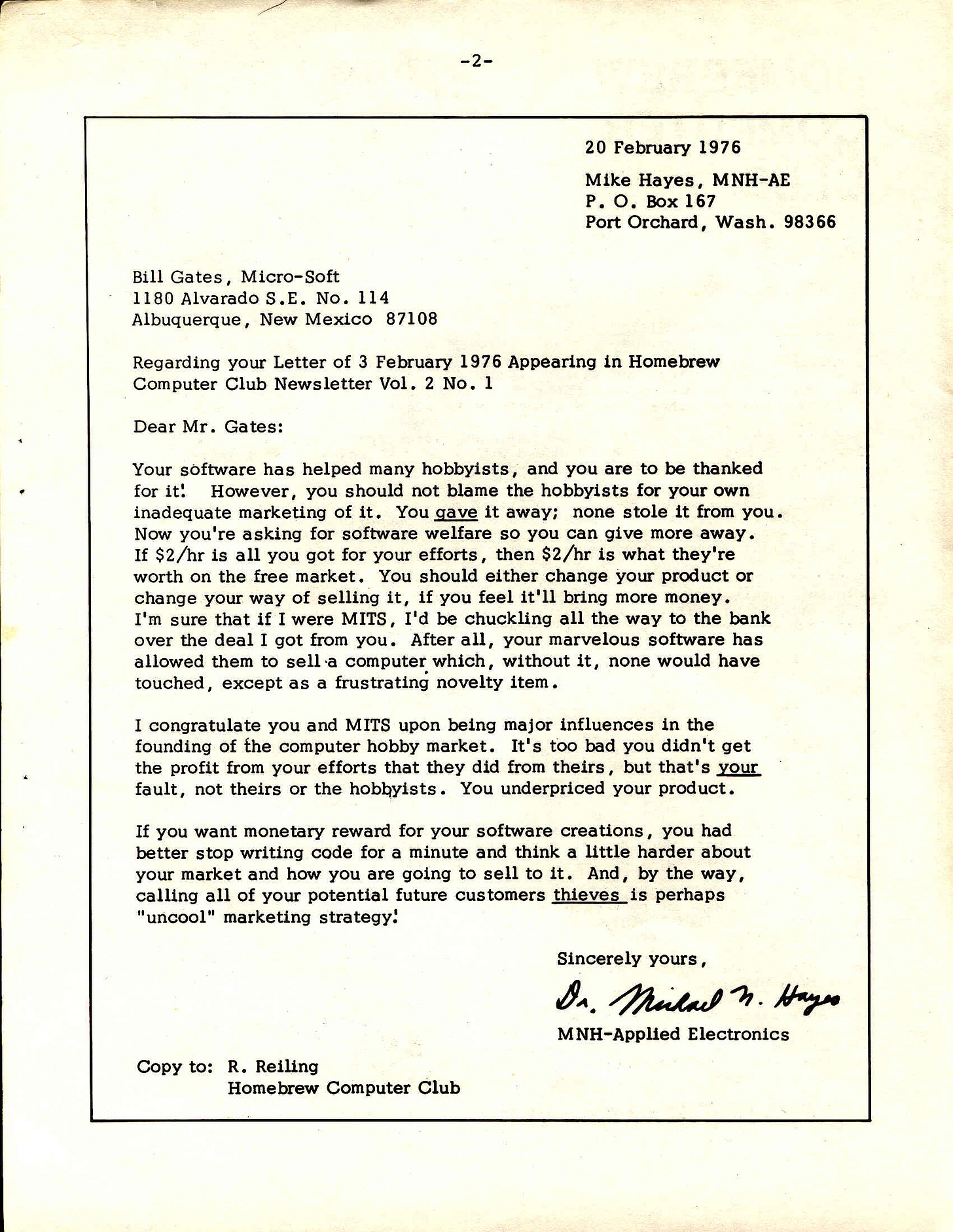

As a follow-up to this open letter from Bill Gates, which was not very well received (to say the least), the following response was published in “The Homebrew Computer Club Newsletter”

The key item is there at the end:

“If you want monetary reward for your software creations, you had better stop writing code for a minute and think a little a harder about your marketing and how you are going to sell it.”

As someone who has been personally yelled at by Bill Gates, I can vividly imagine Bill fuming over this response. Just the same… I guarantee you he took the lesson to heart.

By the end of the 1970s, two things were crystal clear:

If it was easy for computer users to make copies of, and share, software… they were going to do that.

Computers were currently designed such that making those copies — be they on floppy, cassette, or in print — was darned easy.

And, at the moment, there wasn’t much companies like Micro-Soft could do about it… except make the occasional deal to bundle software with hardware. And complain. A lot.

The 1980s: Duplicate floppy before using!

As the 1980s hit, the world of Personal Computers absolutely exploded. Hardware from Commodore, Apple, IBM, Atari, Tandy, and so many others flooded the market… and computer users purchased them in droves. New computer users arrived, by the millions.

More computer users meant more people buying computer software.

In fact, the number of computer users was becoming so large, so rapidly, that software sales exploded as well — even if a large percentage of users copied software instead of purchasing it.

During the 1980s, software sales used a bit of an honor system. Software developers and publishers relied upon the honesty — and honor — of people to purchase a game, utility, or operating system… rather than copy it.

This was mostly by necessity more than choice. The reality was that it was incredibly hard to stop people from making copies of software.

Just the same, many publishers embraced the ability to copy software media — even going so far as to recommend that people make backup copies of cassettes and floppy disks… you know… just in case something bad happened to the original. Some software would even help you to create backup floppies during an installation process.

And, why not? If people could make copies anyway… why not encourage your customers to use that ability to make life easier for themselves (and earn a little goodwill in the process)?

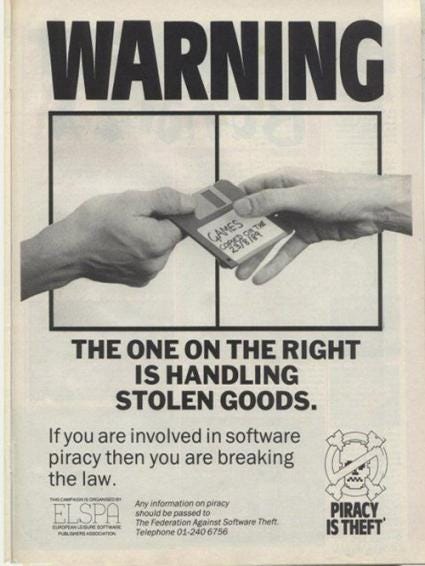

While all of this was going on, some companies were actively working on ways to limit the ability for computer users to be able to copy the floppy disks they purchased. They saw what happened to Micro-Soft in the 1970s… and they felt that, if they could stop people from copying floppies, their sales would skyrocket.

Numerous “copy protection” schemes were attempted in order to make an individual floppy disk “un-copy-able”. With varying level of success.

Intentional disk errors

Extra tracks on disk

Custom disk formats

And numerous other copy protection systems such as SpiraDisc for the Apple II

As the decade marched onward, companies continued their quest to perfect copy protection… and they continued to fail. Every time a new copy protection system was created, the computer hobbyists would find a way around it.

Some developers took a different approach: Providing serial numbers and product keys, or built-in functionality in their software that would ask a user to look up a word at a specific place in the software manual. These sorts of copy protection systems still allowed users to make backup copies of their software… but made it challenging to share those copies with others.

Companies tried to keep people from copying software. They tried very, very hard. But people had floppy drives. So it kept happening.

The 1990s: Don’t copy that floppy!

Those cursed floppy disks! It seems like no copy protection scheme could stop people from copying software as long as they had one of those dastardly floppy drives! Something must be done!

So, in 1992, the Software Publishers Association (a trade group of software companies, including Microsoft) launched a super-hip (*cough*) ad campaign to convince people to stop copying software: Don’t Copy That Floppy.

Complete with a totally rad, not at all tone-deaf music video, the Don’t Copy That Floppy campaign sent VHS tapes to schools across America.

As you would expect… this ad campaign didn’t do much to stop people from copying them-thar-evil floppies. If anything, it reminded people how easy it was to copy software from their friends and relatives (and schools).

Plus… they got a good laugh at the music video.

But what could be done? Even as new types of physical media were created — such as CDs and DVDs — easy ways to copy them cropped up almost as quickly as the formats themselves were created.

Zip disks. Jaz drives. USB thumb drives. Compact Flash drives. All of these could be copied as well… so clearly none of those will solve the problem. Why even bother shipping software on those media?

No. A solution needed to be found. One that would completely eradicate the menace of physical media once and for all.

Luckily, as the 90s pressed on, a solution appeared to be presenting itself.

The Internet: Solution to “The Media Copy Problem”

The Internet, while not ubiquitous in the late 1990s, was gaining traction. And it provided software publishers with some big advantages over using physical media:

Digital purchasing and downloading of software

On-Line verification systems and validation of purchases

Tracking, data collection, related services, and other new, potential revenue streams

Early “end-of-life-ing” of software (read: forced upgrades)

This, for the developers and publishers who were concerned with piracy and copying of their software, seemed like the solution to all of their problems.

No more needing to worry about those pesky floppies and CDs!

There were just two problems that stood in their way:

Not enough people had Internet access to be able to drop physical media entirely and…

People were not accustomed to ideas like digital-only purchasing, online software, and DRM.

From the late 1990s through the early 2000s this problem was tackled, head-on.

Internet access was already growing — thanks in part to public interest in Internet service, and also thanks to government and corporate subsidies to help roll out increasingly easy Internet connectivity.

And the majority of the public was ready to jump on the idea of On-Line software stores. They were, quite frankly, too darned convenient to pass up. Plus… many publishers were intentionally ceasing physical production of software media. Thus computer users were forced to turn to digital-only stores to get the software they needed.

When was the last time you went to a software store? Or saw a large software section at an electronics store? The fact is, the publishers quickly made sure there was no physical media options available.

Today: No physical media, DRM’d downloads only

As the 2000s pressed on, their goals were achieved. The problems that Micro-Soft faced in the 1970s — being burdened by easily copied physical media — had been almost completely solved.

Physical media has been all but eradicated. And it only took 30 to 40 years to accomplish.

Floppy disks, CDs, DVDs, and other such forms of physical data storage are now rarely used for software (except by those interested in retro computing).

And the public, by and large, has become accustomed to not purchasing software on physical media. Most computer users are now comfortable with the idea of having purchased software wrapped in DRM and tied to user accounts and devices (and requiring Internet access).

Even though some physical media still exists — such as SD cards and USB thumb drives — the industry has made a point of not shipping on such media (even though it would be easy and relatively inexpensive to do so)… as those would become instantly susceptible to the same weakness as floppy disks: they can be copied and shared far too easily.

While software piracy still exists — and likely always will — it has become far less common and less accessible to the average computer user than it was in the 1980s.

What this means for us, the users

While all of this may be celebrated by the software industry — and they certainly have seen extreme profits over the recent years — the downsides are… not good. Bordering on devastating.

Our software is increasingly reliant on Internet connectivity.

When a server goes down, we lose access to our software.

When an online store goes offline, we lose access to our software.

When an account is revoked, we lose our software.

When we lose access to the Internet (temporarily or permanently), we lose access to our software.

Creating backups is increasingly difficult.

This has ramifications not just for us, in the present, but for future historians as well. How will many applications and games of 2022 be able to be used in 2050?

What if you need to restore some software when you don’t have Internet access? Or the app store you used is offline or, worse, gone completely?

These aren’t theoretical issues — they are already cropping up in the real world.

The Nintendo eShop (an On-Line store for multiple Nintendo consoles) is discontinued and going completely offline over the coming months. At which point games purchased there will no longer be available.

Software purchased in the early days of the Mac App Store, Android App Store and others are (in a large number of cases) no longer available.

Will the Microsoft Store, iOS App Store, Steam, and others continue to exist 100, 50, or even just 10 years from now? How about 5 years from now? Considering the rapidly changing world of tech… are you truly confident that those systems will continue existing for any length of time (and continue to support the exact version of the software you purchased on the system you purchased it on)?

Recent history tells us this isn’t going to go well for us.

And, think about this: In less than 40 years we went from “make sure to make a backup of your floppy disk” to “you’ll have no physical copy of your software and you’ll be happy.” What happens 40 years from now? I shudder to think how much worse it could get.

While the problems with copying software in the 1970s and 1980s has been (mostly) solved… the ramifications of the way it was solved has been nothing short of devastating for computer users of both the present and future.

But the reality is this: The software companies that continue to make backing up software difficult… simply do not care. They’re making too much money, right now, to care about either the future or us, the users.

To Microsoft, Apple, Google, Valve, and the rest: Prove me wrong.

This is a free article. Want more of the truly independent Tech Journalism from The Lunduke Journal? Lunduke Journal subscribers get a mountain of goodies — and have access to all of the in-depth, premium articles, such as these recent ones:

![WANTED: “Dial-A-Pirate” code wheel for Monkey Island [FOUND!] - Adventure/Lucasfilm Games - Official Thimbleweed Park Forums WANTED: “Dial-A-Pirate” code wheel for Monkey Island [FOUND!] - Adventure/Lucasfilm Games - Official Thimbleweed Park Forums](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VH3p!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa8de2258-47d1-427f-a11f-2395ecddbcb5_650x650.jpeg)

Also, you should note that only the Wii U and 3DS eShop is being discontinued. The Switch is still supported, and Nintendo claims that downloads for previous generation systems will continue to work. Just saying, you're leaving out some nuance with that line.

All I'm hearing is that Stallman was right: if the users don't control the software, the software controls the users. Free (as in freedom) software doesn't suffer from any of these problems.